Aaaand we’re back.

I took some much needed time off during the holidays, the unintended consequence of which was that I didn’t post on my blog for about two weeks. But I’m back to working a normal schedule now, so fired up the laptop and I’m getting back into writing, too.

The holiday break was great. Our youngest came up from downstate, where she’s lived since graduating from college, and spent a week with us over Christmas. So, we hung out, ate a lot, got together with family, watched football, and did all that holiday stuff. (Professional writing tip: always use hung as the past tense of hang, unless you’re talking about an execution. Then it’s hanged.)

And, speaking of football, my and my daughter’s alma mater, the University of Illinois, beat Tennessee in the Music City Bowl on December 30 and the game was actually fun to watch. And then Indiana (the bandwagon I jumped on this season) won the Rose Bowl, which was fun too. I’m not going to pretend I understand how these college football playoffs work, but the Hoosiers winning a national title would really be something.

On top of all that, we’ve been dealing with these feral cats who’ve more or less taken over our home, which has been … a little challenging. Between corralling, or attempting to corral, three new cats for vet appointments, we’ve had to negotiate an uneasy peace between them and our two older cats, Gordy and Waffle, who are still a bit confused by all of this. And, because no good deed goes unpunished, the mom cat is now in heat (thankfully, she’s going to be spayed next week — not a moment too soon). It’s not her fault, of course, but the wailing and gnashing of teeth is something to behold. Especially at three o’clock in the morning.

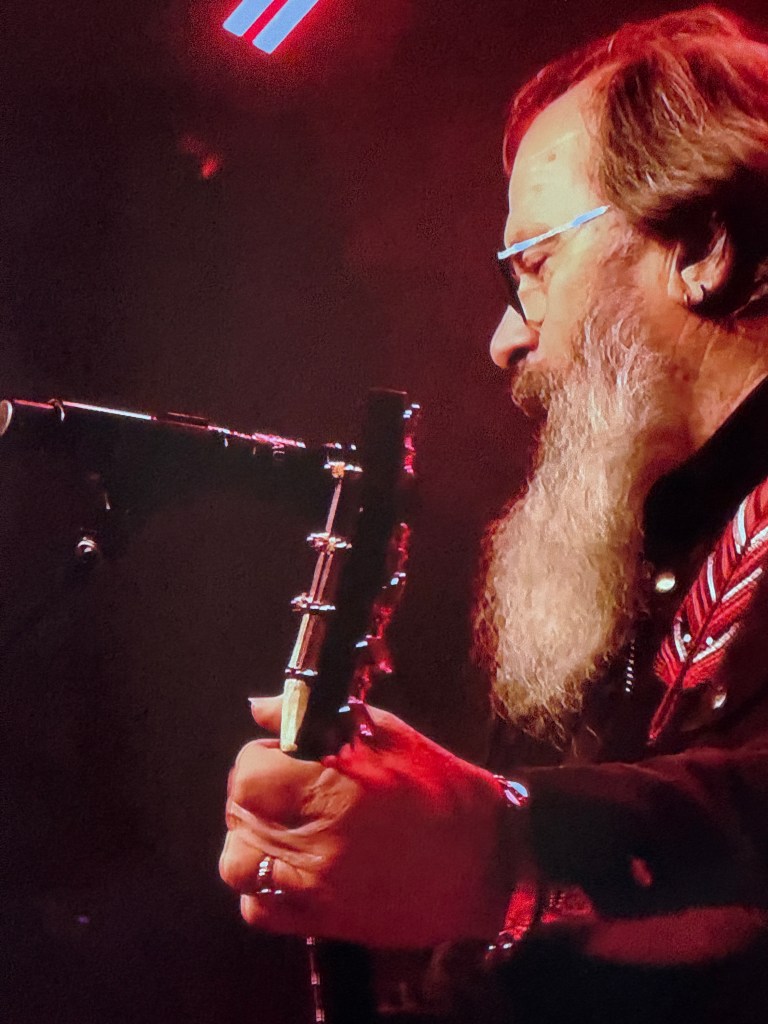

Nonetheless, I found the time to play guitar over the past few weeks (much to the new and old cats’ chagrin), aided by two Christmas gifts. One was a present to myself: a proper guitar stool (see the picture above). The other, thanks to my wonderful and long-suffering wife, was an acoustic guitar cleaning kit, as a result of which my Ibanez Art Wood is looking pretty spiffy (again, see picture above).

So, I may or may not torture you with more guitar playing videos in the new year, but, hey, practice makes perfect.

I’m also working on a piece that I’ve been struggling with for the past month or so, but I hope to get it up soon. It’s my take on everybody’s favorite Christmas song, the Pogues’ “Fairytale of New York.” It’s … complicated.

Anyway, I hope you had a chance to rest and relax over the past couple of weeks. Let’s hope 2026 is less challenging and more uplifting than 2025. I think we all deserve that.